Fossil Friday #3 - Helicoprion

Palaeontology shows us a wide range of species that may not have even been imaginable had it not been for fossil evidence. The same could be said about some of the wonderful ocean life that lives on our planet even today. When looking at prehistoric wildlife, some of the wildlife that used to live in earth's oceans took incredible forms that would look out of place in our world today. Many of these animals are difficult to reconstruct even with fossil evidence that has been uncovered, and such has been the case with the Permian eugeneodont, Helicoprion.

The signature feature of Helicoprion, the tooth-whorl, is what has made it difficult to reconstruct. Being a cartilaginous fish, the rest of the body is rarely preserved, so the tooth-whorl is the only evidence that exists of this fish. What has also made this so puzzling for reconstruction is the fact there is nothing alive today that resembles this feature, which makes it difficult to apply the theory of uniformitarianism; the idea that the present can tell us about the past.

The first Helicoprion specimen was discovered in Western Australia in 1886. It was first described by British geologist, Henry Woodward, as Edestus davisii, a genus of fish that is today known to be a close relative of Helicoprion. Another specimen was discovered in 1899, in the Ural mountains of Russia by Alexander Karpinsky, who then classified the new find as Helicoprion bessonowi, and the already-known 1886 specimen under the same genus name, Helicoprion. Although H. davisii was discovered first, H. bessonowi is the type species, as it the was the first to be recognised under the Helicoprion genus. Since this time, tooth-whorls of this prehistoric fish have been discovered in many locations around the world, including China, Japan, Mexico, Norway and the United States. This suggests it was a rather successful group, filling niches in many areas of the world's oceans and surviving for around 20 million years (290 - 270ma).

Helicoprion davisii tooth-whorl fossil (University of Nevada, 2018).

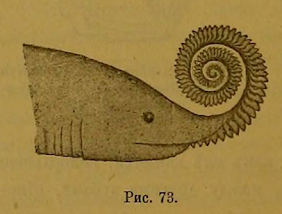

Reconstructions of this animal have been debated since its discovery. Early theories have suggested that the tooth-whorl was actually a defensive tail spine, like those seen in rays, or that it even ran across the pectoral fin. It was widely accepted to represent a jaw after Karpinsky's description in 1899, however the debate did not end there. It was first thought that the tooth-whorl was part of the maxilla, and curved outwards. Karpinsky then published a paper in 1911, illustrating the whorls as part of the dorsal fin, meaning at this point, the whorl had been placed on just about every part of Helicoprion, and was yet to be widely agreed on. Today, it is accepted that the tooth-whorl was part of the mandible, but this was not a widely accepted theory until 1966, when a Carboniferous eugenodont was described, the Ornithoprion hertwigi. This animal had evidence of the tooth-whorl being placed in the mandible and curving inwards towards the maxilla. This is an example of looking at other related taxa in order to draw conclusions on a particular genus or species. There has been evidence of wear on Helicoprion tooth-whorls, suggesting it lay at the front of the mouth, where it would have been exposed to the elements of the ocean, and fed on fish and squid. This would make their tooth placement similar to that of modern cetaceans, such as sperm whales, which only have teeth in the front part of the jaw, and also feed on fish and cephalopods.

(Eastman, 1900). (GeologyIn, 2020).

Despite its morphology, Helicoprion is not classified as a true shark and is not a part of the same lineage as modern sharks. It is classed as a Eugeneodontid, an extinct order of cartilaginous fish, that are all recognised by their variations of tooth-whorls.

The changing opinion on the reconstruction of this ancient fish highlights what I believe is one of the reasons why palaeontology is so fascinating. No matter the evidence that we have of an organism, we can never know for sure that we've got it right, hence the fact that there is always room for more study, even if the only evidence we have is of one part of the body.

References

Eastman, C.R. (1900) “Karpinsky's genus Helicoprion,” The American Naturalist, 34(403), pp. 579–582. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/277706.

The Helicoprion was a shark with a buzzsaw in its mouth (2020) Geology In. Available at: https://www.geologyin.com/2020/11/helicoprion-spiral-mouthed-killer.html (Accessed: January 12, 2023).

Kent, J.T. (2018) Mineral Monday: Helicoprion Fossil, Nevada Today. University of Nevada, Reno. Available at: https://www.unr.edu/nevada-today/news/2018/mineral-monday-helicoprion (Accessed: January 12, 2023).

Lebedev, O.A. (2009) “A new specimen of Helicoprion karpinsky, 1899 from Kazakhstanian Cisurals and a new reconstruction of its tooth whorl position and function,” Acta Zoologica, 90, pp. 171–182. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-6395.2008.00353.x.

Comments

Post a Comment