Fossil Friday #2 - Paraceratherium

One of the main assets of ancient life that first drew me to Palaeontology as a child is the sheer size of some of the animals that used to walk this very earth. Of course, the dinosaurs are the most famous example of this and are a group that contains the largest terrestrial animals to ever grace our planet. It is not just the dinosaurs, however, that could grow to such sizes that are almost unimaginable to envision in today's world. More recently than the dinosaurs, there were some truly outstanding now-extinct mammals that would dwarf any other land animal that is alive today. One of the most extreme examples of this is the Paraceratherium.

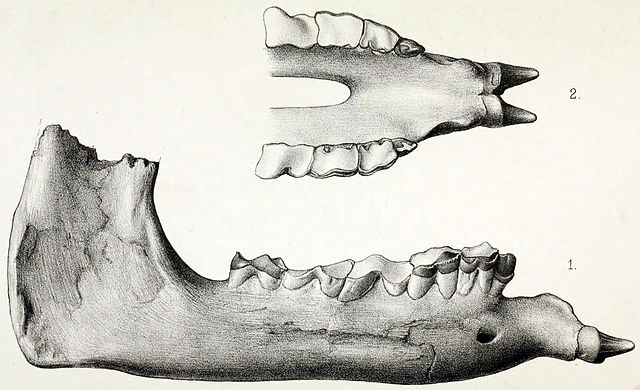

This truly remarkable animal was first discovered in Pakistan, a place where many impressive mammal fossils have been discovered, such as the ancestors of modern-day whales, which are more resemblant of dogs and rodents, rather than marine mammals. The first studied specimens of Paraceretherium were discovered by British geologist, Guy Ellcock Pilgrim in 1907. The find included fragments of the jaws and teeth. Like many new fossil discoveries at the time, it took a number of years before its final classification was widely accepted. At first, it was thought that these belonged to a new species of Aceratherium, a much smaller genus of Rhincerotidae. Three years after these events, another British scientist, Clive Forster-Cooper had discovered more partial specimens in Pakistan during an expedition. These were seen to be of the same genus as Pilgrim's finds and were consequently reclassified under a new genus, Baluchitherium. This genus name is now invalid, as it has since been classified as the same genus as Indricotherium, another now-invalid name coined by Russian scientist, Aleksei Alekseeivich Borissiak in 1916, after the discovery of a skull-less skeleton. The species of these genera are now classified under the genus, Paraceratherium. Despite the changes in classification, the type species is the Paraceratherium bugtiense, discovered and described by Pilgrim in 1908.

To many people, the morphology of Paraceratherium may cause them to believe that it is related to modern-day giraffes or elephants. It is, however in fact an ancester of the Rhinoceros. Rhinocerotoidea, the family that contains all living Rhinos, split from the same lineage as Paraceratheriidae during the early Eocene epoch, roughly 50 million years ago. The most recent phylogenetic studies show the diversity of these two groups and shows how they are related to one another. (Deng et al, 2021).

Paraceratherium possessed a type of defence from predators that have only been seen in select species throughout the earth's history; they were too large for any of the predators in their habitat to cause a threat to them. This allowed them to become a successful group of animals and spread throughout the continent of Asia. It has been estimated that they could reach a mass of 20 tonnes, which is close to the absolute maximum that it is estimated for a terrestrial mammal to reach (Clauss et al, 2003). Fossil evidence would also suggest that the largest could reach heights of 6 metres, similar to a modern giraffe, but Paraceratherium were much heavier and longer.

References

Putshkov, P. V. (2001)."Proboscidean agent of some Tertiary megafaunal extinctions". Terra Degli Elefanti Congresso Internazionale: The World of Elephants: 133–136.

Strauss, B. (2017) Indricotherium (Paraceratherium) Facts, ThoughtCo. ThoughtCo. Available at: https://www.thoughtco.com/indricotherium-paraceratherium-1093225 (Accessed: January 5, 2023).

Werdelin, L. and Peigne, S. (2010) "Cenozoic Mammals of Africa" in Carnivora, pp. 603-657.

Comments

Post a Comment